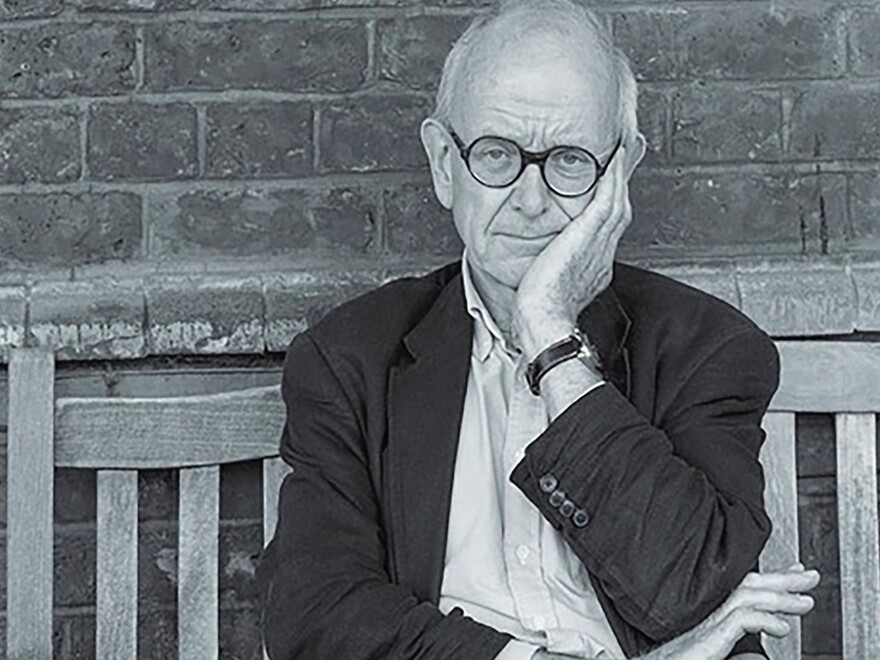

Renowned British physician Henry Marsh was one of the first neurosurgeons in England to perform certain brain surgeries using only local anesthesia. For over 30 years, he also made frequent trips to Ukraine, where he performed surgery and worked to reform and update the medical system.

As a surgeon, Marsh felt a certain level of detachment in hospitals — until he was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer at age 70. Though he continued working after his diagnosis, it was sobering to interact with the hospital as both a doctor and a patient.

"I was much less self-assured now that I was a patient myself," he says. "I suddenly felt much less certain about how I'd been [as a doctor], how I'd handled patients, how I'd spoken to them."

In the memoir, And Finally, Marsh opens up about his experiences as a cancer patient — and reflects on why his diagnosis happened at such an advanced stage.

"I think many doctors live in this sort of limbo of 'us and them,' " he says. "Illness happens to patients, not to doctors. Anecdotally, I'm told that many doctors present with their cancers very late, as I did. ... I denied my symptoms for months, if not for years."

Marsh's cancer is in remission now, but there's a 75% chance that it will return in the next five years. It's an uncertainty that Marsh has learned to accept.

"For the last few weeks I've been in this wonderful Buddhist Zen-like state," he says. "At the moment, I'm really very, very happy to be alive. But that's really only possible because I've had a very complete life and I have a very close and loving family and those are the things that matter in life."

Interview Highlights

On seeing his own brain scan, and being shocked at its signs of age

It was the beginning of my having to accept I was getting old, accept I was becoming more like a patient than a doctor, that I wasn't immune to the decay and aging and illnesses I've been seeing in my patients for the previous 40 years. So it was actually terribly frightening looking at the scan, crossing a threshold, and I've never dared to look at it again. It was just too upsetting. In retrospect, it probably wasn't that big a deal. Probably, if I had seen that scan at work, I'd have said, "Well, that's a typical 70-year-old brain scan."

On continuing to work in the hospital after being diagnosed with cancer

As a doctor, you're not emotionally engaged in any way. You look at brain scans, you hear terrible, tragic stories and you feel nothing, really, on the whole, you're totally detached. But what I found was when I was at some teaching meetings and they would see scans of a man with prostate cancer which had spread to the spine and was causing paralysis, I'd feel a cold clutch of fear in my heart. ... I'd never felt anxious going into hospitals before, because I was detached. I was a doctor. Illness happens to patients, not to doctors.

On getting diagnosed at age 70, and feeling his life was complete

We all want to go on living. The wish to go on living is very, very deep. I have a loving family. I have four grandchildren who I dote on. I'm very busy. I'm still lecturing and teaching. I have a workshop. I'm making things all the time. There are lots of things I want to go on doing, so I'd like to have a future. But I felt very strongly as the diagnosis sunk in that I'd really been very lucky. I'd reached 70. I had a really exciting life. There are many things I was ashamed of and regretted, but I like the word "complete." Obviously, for my wife's sake, my family's sake they want me to live longer and I want to live longer. But purely for myself, I think how lucky I've been and how often approaching the end of your life can be difficult if there's lots of unresolved problems or difficult relationships which haven't been sorted out. So in that sense, I'm ready to die. Obviously, I don't want to, not yet, but I'm kind of reconciled to it.

On not fearing death, but fearing the suffering before death

I hate hospitals, always have. They're horrible places, though I spent most of my life working in them.

I hate hospitals, always have. They're horrible places, though I spent most of my life working in them. It's not really death itself [I fear].

I know, as a doctor, that dying can be very unpleasant. I'm a fiercely independent person. I don't like being out of control. I don't like being dependent upon other people. I will not like being disabled and withering away with terminal illness. I might accept it, I don't know. You never know until it happens to you. And I know from both family and friends and patients, it's amazing what one can come to accept when you know your earlier self would throw up his or her hands in horror. So I don't know. But I would like the option of assisted dying if my end looks like it would be rather unpleasant.

On why he supports medically assisted death

Medical law in England [is that it] is murder to help somebody kill themselves. It's ridiculous, is the short answer. Suicide is not illegal, so you have to provide some pretty good reasons why it is illegal to help somebody do something which is not illegal and which is perfectly legal. And opinion polls in Britain always show a huge majority, 78%, want the law to be changed. But there's a very impassioned, dare I say it, fanatical group — mainly palliative care doctors — who are deeply opposed to it. And they've got the ear of members of parliament.

They argue that assisted dying will lead to coercion of what they call vulnerable people. You know, old, lonely people will be somehow bullied by greedy relatives or cruel doctors and nurses into asking for help in killing themselves. But there's no evidence this is happening in the many countries where assisted dying is possible, because you have lots of legal safeguards. It's not suicide on request. You can make the safeguards as strong as you like: You have to apply more than once in writing, with a delay. You have to be seen by independent doctors who will make sure you're not being coerced or you're not clinically depressed. So it's only a very small number of people who opt for it, but it does seem to work reasonably well without terrible problems in countries where it's legal. And there's no question of the fact, even despite good palliative care — although some palliative care doctors deny this — dying can be very unpleasant, both not so much physically as the loss of dignity and autonomy, which is the prospect that troubles me.

On knowing when it was time to stop doing surgery

I stopped working full time and basically operating in England when I was 65, although I worked a lot in Kathmandu and Nepal and also, of course, in Ukraine. And what I always felt as a matter of principle, it's best to leave too early rather than too late. As in anything in life, whether it's a dinner party or your professional life itself, it's best to leave too early rather than too late. To be honest, I was getting increasingly frustrated at work. I mean, I'm a great believer in the British National Health Service, but it's become increasingly bureaucratic. And psychologically, I was becoming less and less suited to working in a very managerial bureaucratic environment. I'm a bit of a maverick loose cannon. Also, I felt it's time for the next generation to take over. And I had become reasonably good at the operations I did. I didn't think I was getting any better. And I had a very good trainee who could take over from me and had actually taken things forward, and particularly in the awake craniotomy practice, he's doing much better things than I could have done. So it felt like a good time to go in that regard.

What really surprises me now is I don't miss it at all. I was completely addicted to operating, like most surgeons. The more dangerous, the more difficult the operation, the more I wanted to do it, the whole risk and excitement thing. One of the most difficult parts of surgery is learning when not to operate. But much to my surprise, I don't miss it — and I don't quite understand that. But I'm very glad. In a funny sort of way, I feel like a more complete human being now that I'm no longer a surgeon. I no longer have a terrible split in my world view between me — and the medical system and my medical colleagues, that is — and patients. So I feel a more whole person.

Thea Chaloner and Joel Wolfram produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Deborah Franklin adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

!["I was much less self-assured now that I was a patient myself," says neurosurgeon Henry Marsh. "I suddenly felt much less certain about how I'd been [as a doctor], how I'd handled patients, how I'd spoken to them."](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/6089559/2147483647/strip/true/crop/5700x4275+0+0/resize/880x660!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2023%2F01%2F30%2Fgettyimages-107217575-033d8d9803b721fe7bbb3f7870efed17d85ed370.jpg)