SAN CASCIANO DEI BAGNI, Italy — Russia's invasion of Ukraine — and decision to throttle natural gas exports to Europe — has sent energy prices and utility bills higher. The rising costs have forced many households to get creative to save money.

In this Tuscan town, some cooks have rediscovered the energy-saving cooking box, a tool their grandparents used during World War II. An enterprising nonprofit here is producing useful — and stylish — insulating boxes that use less gas than traditional Italian cooking.

Sheep graze on sloping pastures in the hilltops that surround this village. The animals are raised for meat, since their wool is poor quality. But Filo & Fibra, a nonprofit cooperative, has found a way to use the sheared fleece.

Gloria Lucchesi, a co-founder of Filo & Fibra — which means "thread and fiber" — invited NPR to her large home on the outskirts of town to demonstrate one of the cooking boxes it produces.

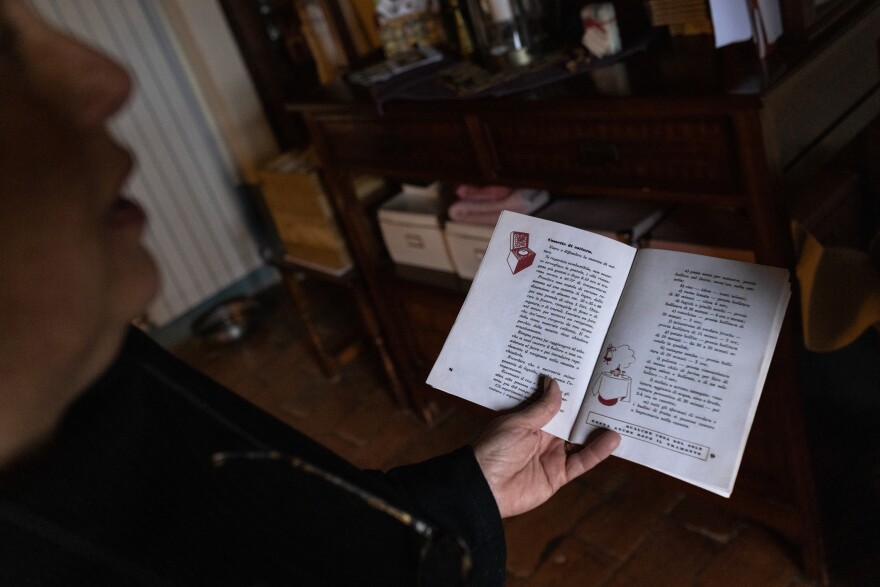

As Lucchesi pulls steaming hot metal pots out of some odd-looking boxes, she says she found a book filled with tips on saving energy and cooking in times of scarcity. The book, published in 1941, belonged to her grandmother.

"My grandmother's booklet described what it called a cooking box made of wood and lined with straw," she says. "We realized that instead of straw, we could use our local wool."

Filo & Fibra is manufacturing two types of insulating boxes: one made from wood, the other from felt. Some have stylish cotton designer patterns on the outside. Each has a thick inner lining made from local wool.

The boxes are virtual portable ovens that use wool's convection properties as a means of slow cooking.

You put your ingredients in a normal pot, says Lucchesi, and first place it on a stovetop.

"You let it come to a boil for maybe 10 or 20 minutes, depending on the ingredients. Then you place the hot pot inside the insulated box and the cooking process continues on its own, slowly over several hours. It's fantastic!" she says.

We sit down to eat in Lucchesi's large kitchen and feast on steaming portions of delicious lentils, beans and potatoes.

Filo & Fibra projects that a family using a cooking box 20 to 30 hours a month will save up to $52 a year on gas bills.

But there may be an even bigger advantage, says Lucchesi's husband, Francesco Asso, who teaches international economics at Palermo University. He says the boxes allow home cooks much more freedom to work or do other things away from home, since they don't have to stay glued to their stovetops.

"We've tested with friends and relatives, cooking the same things like vegetables or legumes, using gas and using the cooking box," Asso says. "And the verdict was always on behalf of the cooking box because the quality is better."

One new convert to the cooking box is Tiziana Tacchi — a renowned chef in the nearby town of Chiusi.

She welcomes NPR in the kitchen of her restaurant, Il Grillo è Buoncantore, which derives its name from a Renaissance song.

When she first tried a cooking box last June, she says she was skeptical.

"But on the second try, I was sold," Tacchi says. "I fell in love with it."

Cooking times are longer than on a stovetop, but Tacchi says the result is excellent. The cooking box surrounds the entire pot with a homogeneous heat source instead of one flame underneath.

"There's no loss of steam," she says. "And the food's nutritional properties are sealed in."

Tacchi lifts the lid of a large steaming pot. She prepared it in the morning, left it for three hours and now it's ready to be served. She's very proud of the result: a Tuscan specialty — a sauce made with a local product — a particularly pleasant-tasting garlic, which is at the base of salsa all'aglione.

Tacchi owns two cooking boxes and says she'll buy more.

"They've totally transformed my life! This is a turning point — in terms of quality, saving time and saving energy," she says.

The day wraps up at yet another restaurant in a rustic setting: Hosteria di Villalba — in the middle of a large forest that straddles the regions of Tuscany, Lazio and Umbria.

NPR has come to taste the results of chef Adio Provvedi's first experience using a cooking box. He prepares a local Tuscan classic, a beef stew braised in Chianti until tender, with lots of black pepper — hence its name, peposo, peppery.

Normally, a peposo would stay on the stovetop for three hours. With the cooking box, Provvedi says he left the ingredients to slow-cook for four hours.

He's unsure whether the timing was right.

The chef and a waiter serve steaming dishes of tender morsels of chuck roast.

The unanimous verdict is "ottimo, perfetto, morbidissimo" — excellent, perfect, very tender.

Fila & Fibra's cooking boxes were presented at the Salon of Taste, organized by an association called Slow Food, in Turin in September.

The target market is families who care about food quality and saving energy, but several restaurants have also started putting in orders. Lucchesi says so far about 100 units have sold, with a wooden box costing up to $250.

But, as Lucchesi says, that's about the same price in Italy as a decent microwave.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.